Summary

A comprehensive, lot-by-lot look at the rich history, cultural evolution, and landmarks of one of NYC's most iconic streets, highlighting its transformation from an immigrant enclave to a vibrant artistic hub.

St. Marks Place has a rich and vibrant history, evolving from an elegant residential district in the early 19th century to a hub of counterculture and artistic expression in the 20th century.

In the early 1800s, St. Marks Place was home to grand Federal and Greek Revival townhouses, attracting wealthy residents. However, by the mid-19th century, the area began to decline, with the influx of German immigrants transforming it into “Kleindeutschland” (Little Germany). Tenement housing and boarding houses replaced the elegant homes, reflecting the changing demographics of the neighborhood.

The 20th century saw St. Marks Place emerge as a center of counterculture and artistic activity. Today, St. Marks Place continues to be a diverse and dynamic neighborhood, blending its historical legacy with contemporary trends. While most of the old-school offbeat shops have closed, the street still retains its edgy and alternative spirit, attracting visitors from around the world.

Below is a lot-by-lot dive into some of the more remarkable history of this storied street.

2 St. Marks Place

Located at 2 St. Marks Place, where a pizza spot now stands, was once the site of a staple haunt for the Beat Generation: Sagamore Diner. This all-night, greasy-spoon diner was where poets, artists, and “respectable bums” (as Jack Kerouac put it) could get cheap coffee, stay warm, and linger for hours without hassle. Locals recall that during the harshest winter days, the diner was a refuge, drawing a unique clientele of artists, writers, students and immigrant laborers seeking companionship, and refuge from barely-heated, cold-water tenement apartments..

Around the corner, the 5 Spot jazz club, originally located at 5 Cooper Square, moved to the ground floor of the St. Marks Hotel (then known as the Valencia Hotel) in 1962. This spot became legendary in jazz history, opening its new doors with a historic seven-month residency by Thelonious Monk, backed by John Coltrane. Monk’s performances here marked his triumphant return to the New York City club scene after a six-year absence due to the loss of his cabaret card. His arrest in 1951 at a segregated hotel in Delaware had kept him out of clubs until he returned with his groundbreaking sound, which sent shock waves through the music world.

The 5 Spot was a cultural crossroads where experimental jazz, known as bebop, incubated ans thrived. Here, intellectuals, artists, students, and beatniks mingled until all hours of the night. Musicians like Ornette Coleman, Charles Mingus, and Cecil Taylor played here, defining the raw, improvisational sound of the era. Charlie “The Bird” Parker, widely regarded as the “Father of Bebop,” was a neighborhood fixture who shared meals and stories with poets, musicians, and factory workers. Parker lived nearby at 57 Avenue B, and his former home is now preserved as the Charlie Parker House museum. During this time, creative expression was often fueled by long nights, but it also came with a darker side. Heroin, long present in the Lower East Side, surged during the 1950s and 60s counterculture era, taking a tight hold on the neighborhood well into the 1970s.

The 5 Spot was a cultural crossroads where experimental jazz, known as bebop, incubated ans thrived. Here, intellectuals, artists, students, and beatniks mingled until all hours of the night. Musicians like Ornette Coleman, Charles Mingus, and Cecil Taylor played here, defining the raw, improvisational sound of the era. Charlie “The Bird” Parker, widely regarded as the “Father of Bebop,” was a neighborhood fixture who shared meals and stories with poets, musicians, and factory workers. Parker lived nearby at 57 Avenue B, and his former home is now preserved as the Charlie Parker House museum. During this time, creative expression was often fueled by long nights, but it also came with a darker side. Heroin, long present in the Lower East Side, surged during the 1950s and 60s counterculture era, taking a tight hold on the neighborhood well into the 1970s.

The Valencia Hotel, occupying the upper floors of 2 St. Marks Place, was known for its revolving door of drifters, addicts, and troubled souls between the 1960s and the 1980s. Notable figures such as William S. Burroughs’s close friend James Grauerholz, as well as punk rocker GG Allin, resided there.

The Valencia Hotel was featured in James Leo Herlihy’s novel Season of the Witch, where characters sought out a life filled with “free love, drugs, and danger.” In 1963, city records show that 2 St. Marks Place had permits for a cabaret, cigar store, and 64 budget hotel rooms. Today, the transformed St. Marks Hotel offers clean, affordable lodging, but the building holds echoes of an era when it was a gritty hub for the Lower East Side’s avant-garde.

4 St. Marks Place

The Hamilton-Holly House, a Federal-style building at 4 St. Marks Place, has a storied history since its construction in 1831. Known for its unusual 26-foot width, three-and-a-half-story height, long parlor floor windows, and unique architectural features like the vermiculated entranceway and double segmental dormers, this building is a rare Federal-era design. The high stoop and peaked roof give it a distinctive look, setting it apart in a neighborhood where few structures of its style remain.

Originally developed by Thomas E. Davis, 4 St. Marks Place was sold in 1833 to Alexander Hamilton Jr., son of Alexander Hamilton, the former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. Hamilton Jr. lived here with his widowed mother and their family for nearly a decade. By 1855, the house had passed to the Van Wyck family, who placed an ad in The New York Times seeking a “respectable middle-aged Scotch or German Protestant woman” for household work—hinting at the genteel standards the house once maintained. But by 1870, the neighborhood’s fashionability had declined, and census records show the building had become a boarding house.

Rumor has long held that James Fenimore Cooper, author of Last of the Mohicans, resided at Hamilton-Holly House in the 1830s, though little evidence supports this claim. During this period, the Hamilton and Holly families occupied the residence, and records do not substantiate Cooper’s presence.

By the 1950s and 60s, Hamilton-Holly House evolved into a hotbed of avant-garde art and countercultural performances. The Tempo Playhouse and New Bowery Theater occupied the space, but it was the Bridge Theater that truly pushed the boundaries of free expression during the Vietnam War era. This theater was integral to the Fluxus art movement, which emphasized group-based, improvised, interactive, mixed-media performances, inspired by artist Allan Kaprow. The Bridge Theater hosted luminaries like Yoko Ono, The Fugs, and Bread & Puppet Theater, marking the house as a significant venue for countercultural art.

In 1965, the theater drew official attention for screening Flaming Creatures, a controversial film by Jack Smith, which depicted provocative scenes and was seized by the police. The organizer, Jonas Mekas, was arrested, and the film was labeled “obscene” by the court. The following year, the theater attracted further controversy when an American flag was burned during a performance; although arrests were made, the charges were later dropped.

Jonas Mekas went on to found the Anthology Film Archives, a center dedicated to preserving and showcasing independent, experimental, and avant-garde cinema. In 1979, it found a permanent home in a former courthouse at 32 Second Avenue, solidifying its place as a cultural landmark in the East Village. The Archives have since become one of the world’s largest collections of avant-garde film, hosting screenings, exhibitions, and preserving important works of independent cinema.

Eventually, amid accusations of police harassment, the Bridge Theater closed, and Hamilton-Holly House began yet another chapter. In 1971, it became home to Trash & Vaudeville, an iconic punk rock clothing store that sold spandex and rock apparel to both famous and everyday patrons.

Today, this historic landmark stands as a testament to the Lower East Side’s layered history—from Federal-era elegance to the bold artistic experimentation that shaped the neighborhood’s identity.

6 St. Marks Place

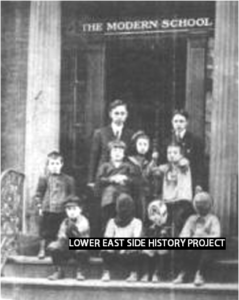

In 1911, 6 St. Marks Place became home to The Modern School, an educational institution founded on the progressive, libertarian principles of Spanish educator and anarchist Francisco Ferrer i Guàrdia. Unlike what one might imagine an “anarchist school” to represent, the Modern School’s mission was not to incite rebellion but to provide working-class individuals with an empowering, class-conscious education that emphasized critical thinking, creativity, and social awareness. This was in line with Ferrer’s vision to foster a free, democratic society through education—a concept radical for its time.

The school’s founders included prominent anarchists such as Emma Goldman, a highly influential and controversial figure in American politics and literature. Known for her impassioned writings and public speaking on workers’ rights, free speech, and women’s liberation, Goldman was both celebrated and vilified. She lived nearby on East 13th Street and edited the anarchist magazine Mother Earth. Her activism extended to controversial acts, including her suspected involvement in the 1901 assassination attempt on President William McKinley, which brought increased government scrutiny to her activities. Goldman’s staunch advocacy ultimately led to her arrest and deportation in 1919 due to her “dangerous” political views.

The school’s founders included prominent anarchists such as Emma Goldman, a highly influential and controversial figure in American politics and literature. Known for her impassioned writings and public speaking on workers’ rights, free speech, and women’s liberation, Goldman was both celebrated and vilified. She lived nearby on East 13th Street and edited the anarchist magazine Mother Earth. Her activism extended to controversial acts, including her suspected involvement in the 1901 assassination attempt on President William McKinley, which brought increased government scrutiny to her activities. Goldman’s staunch advocacy ultimately led to her arrest and deportation in 1919 due to her “dangerous” political views.

Philosopher Will Durant, who would go on to become famous for The Story of Civilization, served as principal. He implemented the school’s hands-on, experimental approach to learning, a progressive model that allowed students to engage with real-world subjects and social issues, preparing them for civic involvement. The curriculum, which might now resemble modern democratic education models, was unusual and groundbreaking in the early 20th century.

The Saint Marks Baths opened in 1913 at 6 St. Marks Place. Originally operating as a Victorian-style Turkish bath, it primarily catered to the neighborhood’s Russian-Jewish immigrant population. These bathhouses were more than places of hygiene; they served as social hubs where immigrants could relax, connect, and preserve elements of their cultural traditions amidst the bustling city.

By the 1950s, as societal norms shifted, the clientele began to evolve. During the day, it maintained its traditional role, but by night, it discreetly attracted a growing homosexual clientele. This transition reflected the increasingly visible gay subculture that was emerging in New York City. By the 1960s, the Saint Marks Baths fully embraced this identity, becoming a space exclusively catering to gay men, and it gained a reputation as one of the city’s most popular gay bathhouses.

In 1979, the bathhouse underwent a significant refurbishment and was rebranded as the New Saint Marks Baths. The redesign introduced modern amenities and aesthetic upgrades, solidifying its place as a premier destination within the LGBTQ+ community. By 1981, its popularity had soared, prompting the purchase of an adjacent building with ambitious plans for expansion. These plans underscored the bathhouse’s role as a vibrant community space during a time when LGBTQ+ visibility and acceptance were growing, albeit slowly.

The bathhouse’s significance extended beyond leisure—it became a cultural landmark of the East Village and a symbol of the sexual liberation movement of the 1970s and early 1980s. However, its legacy was complicated by the arrival of the AIDS crisis in the mid-1980s, which profoundly reshaped attitudes toward spaces like the New Saint Marks Baths.

In later decades, the building housed Kim’s Video, a beloved institution for cinephiles, specializing in rare and independent films. Kim’s Video was a legendary institution on St. Marks Place from the 1980s until its closure in 2009. Founded by Korean immigrant Yongman Kim, it began as a small electronics shop but quickly became known for its video rentals and rare, hard-to-find films. Over time, Kim’s expanded to stock an impressive, eclectic collection, including foreign films, cult classics, obscure documentaries, and avant-garde cinema. Its selection of VHS tapes, and later DVDs, appealed to cinephiles and film students, making it a beloved cornerstone of downtown culture.

Customers included artists, filmmakers, and students who found a treasure trove of niche films that were nearly impossible to find elsewhere. The store’s atmosphere was uniquely chaotic, with towering shelves crammed full of titles and handwritten recommendations from the staff, who were as passionate about film as the clientele. Many regulars recall the distinct smell of the tapes and the labyrinthine layout of the store, which only added to its mystique.

When Kim’s Video closed its doors in 2009, the fate of its vast collection became a cultural story of its own. Unable to find a local organization or institution willing to preserve it, Yongman Kim ultimately donated over 55,000 films to the Italian city of Salemi, Sicily. There, the collection was meant to be preserved and made available to the public, though logistical and funding challenges have since limited its accessibility. In 2018, however, portions of Kim’s Video collection made a return to Manhattan as part of an installation at the MoMA PS1 in Queens, where the spirit of Kim’s legacy lives on in New York’s art scene.

8 St. Marks Place

At 8 St. Marks Place, the history of a single address tells a tale of social reform, controversy, and the immigrant experience in New York City. The Italianate-style building that stands here today (built around 1889) replaced an earlier four-story row house with an eclectic past.

In the 1860s and 70s, this site housed the office of Madame Van Buskirk, a well-known and controversial figure who provided abortion services at a time when the procedure was unregulated and socially fraught. Madame Van Buskirk, like other practitioners of the time, operated in a precarious legal landscape; although abortion was technically legal before “quickening” (the first fetal movements), public opinion began shifting drastically following a series of sensational cases in which patients suffered severe injury or death. These high-profile cases drew media and public scrutiny, eventually leading to stricter laws and the outlawing of abortion by 1876.

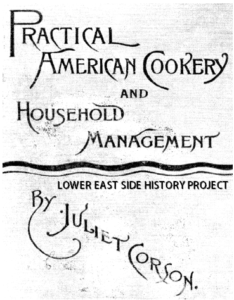

After abortion services were outlawed, the space took on a very different role under Juliet Corson, an innovative educator and reformer who opened the New York Cooking School here. Founded in the mid-1870s, Corson’s school was the first in the United States to offer formal culinary training and was pivotal in establishing cooking as a respected profession. Corson was a champion of accessible, nutritious meals, particularly for low-income families, and she used her platform to publish pamphlets and guidebooks like Cooking Schools and What They Do, advising families on preparing nourishing meals on very limited budgets. Her work went on to inspire the development of cooking schools across the country and underscored the importance of domestic science in empowering women.

By the 1880s, the New York Cooking School had moved on, and the space transitioned into La Trinacria, an Italian restaurant that became infamous for a darker chapter in New York’s criminal history. In 1888, La Trinacria was the site of the first recorded mafia-related murder in the United States. Antonio Flaccomio, an Italian immigrant, was brutally stabbed to death by the Quarteraro brothers following a night of heavy drinking. This incident, which the newspapers covered extensively, was the first time the word mafia appeared in American press—a chilling foreshadowing of the influence organized crime would later wield. Following the murder, one of the Quarteraro brothers escaped to Sicily disguised as a priest, while the other stood trial but was released due to a “lack of witnesses.”

12 St. Marks Place

Constructed in 1888, 12 St. Marks Place stands as an architectural and cultural testament to New York’s German-American history. Designed by German-American architect William C. Frohne, this building served as the headquarters of the German American Shooting Society (Deutscher Schützenbund), a prominent social organization in the German community. As a key part of “Kleindeutschland” (Little Germany), this structure once housed 24 offices for various German and Slavic businesses. The Society provided a social space for German immigrants to gather, uphold their traditions, and share in cultural activities. Although it wasn’t a shooting range, it hosted social events centered on marksmanship, a valued German pastime, and became a community hub during the height of Little Germany.

Many German immigrants arrived in New York in the mid-19th century, fleeing the economic and political instability caused by the failed German Revolution of 1848-49. Known as the March Revolution, this movement attempted to unify the fragmented German territories and implement democratic reforms. When conservative forces ultimately crushed the revolution, many political activists, intellectuals, and revolutionaries—dubbed the “Forty-Eighters”—fled to the United States, bringing with them progressive political ideals. They would go on to play prominent roles in American social, political, and labor movements, infusing their new communities with values of democracy and social reform.

Economic hardship also drove German families across the Atlantic. Industrialization, crop failures, and food shortages forced many farmers and tradespeople to seek opportunities in America, where land was abundant and labor was in high demand. By the 1860s, over a million Germans had settled in the United States, creating one of the first foreign-language neighborhoods in the country. Little Germany became a lively cultural enclave with German-language newspapers, schools, churches, and theaters. The area was known for its German bakeries, beer halls, and shops, which brought a distinct flavor to the East Village.

The decline of Kleindeutschland is often attributed to the tragic General Slocum steamboat disaster of 1904, when over 1,000 members of a predominantly German church community perished in a fire on the East River. This event dealt a major emotional blow to the close-knit German-American community, but it was only one part of a larger trend that had already begun decades earlier.

Starting in the late 19th century, a significant influx of Eastern European Jewish immigrants – thought of as being lower class – began reshaping the character of the Lower East Side. This change put pressure on established German families, who were already seeing their old neighborhood grow more crowded and competitive for housing and business opportunities. As Eastern European Jewish immigrants settled in, they brought their own languages, customs, and religious practices, leading many German-Americans to seek new neighborhoods with a familiar cultural identity, such as Yorkville on the Upper East Side, which became a new hub for German-American life.

13 St. Marks Place

In the 1960s, this building became home to comedian Lenny Bruce, a cultural icon known for pushing the limits of free speech and challenging conventional comedy standards. A trailblazer in stand-up, Bruce, born Leonard Alfred Schneider on Long Island, used humor to tackle taboo subjects like organized religion, politics, and social hypocrisy, rejecting the sanitized comedy style of figures like Bob Hope. His raw, unfiltered routines influenced future generations of comedians like Richard Pryor, George Carlin, and Howard Stern, who credit Bruce with opening doors for more fearless, socially engaged comedy. Bruce’s work laid the foundation for the comedic freedoms enjoyed by comedians today, paving the way for bolder expressions of social and political satire.

Bruce’s career and life were marked by controversy and frequent arrests on obscenity charges, a testament to the era’s resistance to his no-holds-barred approach. In Cold War America, his bold content led to multiple arrests across the U.S., culminating in a 1964 obscenity trial at the New York State Supreme Court. Before the trial concluded, however, Bruce died from a drug overdose—a tragic end that punctuated his struggle for artistic freedom. In 2003, nearly 40 years later, New York granted him a posthumous pardon, the first of its kind in the state, symbolizing a recognition of his fight for free speech.

St. Marks Place, along with the East Village at large, also became a hub for the Yippie movement (Youth International Party), a radical counterculture group that emerged in the late 1960s. Yippies advocated for freedom of expression, anti-war protest, and anti-establishment values, often blending satire with political activism. St. Marks became a focal point for these activists, who used guerrilla theater, street demonstrations, and artistic expression to protest social issues. Figures like Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin led the Yippie movement, engaging in actions that pushed the boundaries of protest and performance. Bruce’s legacy of defying social norms and daring to speak out influenced the Yippies’ style and ethos, shaping St. Marks Place into a battleground for creative rebellion against mainstream American values during this era.

Both Bruce’s pioneering comedy and the Yippies’ audacious activism contributed to the rich, complex legacy of St. Marks Place as a space where freedom, creativity, and resistance against convention thrived.

17 St. Marks Place

In 1885, this building became the site of the first Hebrew-Christian Church in America, an institution dedicated to converting Jews to Christianity. The church’s original façade featured two stained-glass windows on the first floor, alongside a sign in Hebrew that read, “For my house shall be called a house of prayer for all religions,” emphasizing its inclusive message.

The church and its mission were realized through the vision and efforts of Reverend Jacob Freshman, who had been conducting sermons and conversions on the Lower East Side for years before securing the building as the church’s headquarters. Purchased for $20,000—a significant sum at the time—the building was designed to house a hall of worship on the first floor, classrooms and conference rooms in the basement, and the Freshman family apartment above.

Reverend Jacob Freshman was the son of Charles Freshman, a Jewish immigrant and rabbi who converted to Christianity and entered the Christian ministry early in Jacob’s life. This familial legacy was central to the establishment of the church, which operated as a bridge between Jewish and Christian communities.

Interestingly, this church took residence in the same building once inhabited by Dr. Somers, a notable clergyman credited with performing the first Jewish-to-Christian baptism in America, adding a layer of historical significance to the location. Dr. Somers’ work predated the Hebrew-Christian Church by several decades and helped pave the way for similar religious conversions in the area.

20 St. Marks Place

The landmarked Daniel Leroy House, built in 1832, is one of the original structures along St. Marks Place constructed by real estate speculator Thomas E. Davis in the 1830s. Like its neighbor at 6 St. Marks Place, the Daniel Leroy House stands on a unique 26′ x 120′ lot and shares many architectural features.

The lower level is faced with distinctive limestone blocks, while the upper levels are made of red brick laid in Flemish bond. The solid limestone steps leading to the lower level have been worn smooth after over 170 years of foot traffic. Remarkably, up to 90% of the original structure remains intact, including the window frames on the upper floors. The French parlor windows on the first floor were added shortly after the building’s construction, and the Italianate-style wooden doors and circular transom above the entranceway were also added later. Despite some redesigns to the interior over the years, much of the exterior remains as it was.

One of the original owners of the house was Daniel Leroy, the husband of Susan Fish, a descendant of Peter Stuyvesant. Susan was the daughter of Nicolas and Elizabeth Stuyvesant-Fish and the sister of Hamilton Fish, a notable American politician.

In 1860, the house became part of the National Guard’s 7th Regiment and was used as a gymnasium annex. The regiment’s headquarters were just around the corner on East 7th Street and 3rd Avenue. According to a New York Times article, the house was used for “sparring, fencing, dressing, bathing, and reading rooms,” providing a space for the regiment’s physical training and social activities.

19-25 St. Marks Place:

Today a sprawling mini-mall with newly designed condominiums on the upper floors, 19-25 St. Marks Place was originally comprised of four separate buildings. Numbers 19, 21, and 23 St. Marks Place were constructed as wealthy townhouses during Thomas E. Davis’ development of the block in 1831.

As the neighborhood evolved, a predominantly immigrant working-class population moved in. By 1870, the Arion Society, a German music club, purchased 19 and 21 St. Marks Place. This was a period when the Lower East Side was a hub for German immigrants, and the Arion Society became an important cultural institution. By 1887, however, the Arion Society moved to new headquarters uptown, and real estate developer George Ehret purchased the properties. Ehret combined the buildings into one large community hall and ballroom, renaming the space Arlington Hall.

Arlington Hall quickly became a popular venue for social and political events, hosting everything from weddings and dances to union conventions. In February 1894, the New York Times reported on a curious event at the hall, noting, “300 pretty girls, each with a book and pencil, & with no end of bewitching smiles, trooped into Arlington Hall…” They were working on behalf of a charity, although the specific purpose of the books and pencils was not explained.

In 1895, the hall also hosted Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who gave a speech about enforcing the Excise Law, which prohibited alcohol sales on Sundays. Despite interruptions from the crowd, Roosevelt received loud applause for his remarks.

Arlington Hall continued to serve as a site for major events throughout the early 20th century. On December 31, 1900, Bishop Henry Codman Potter delivered a New Year’s Eve dinner speech addressing social reform. Later, in October 1905, William Randolph Hearst used the hall to offer a $1,000 reward for evidence of voter fraud in a local election. The hall also hosted community celebrations, including a Twelfth Night event in January 1912 featuring a 100-pound cake.

However, Arlington Hall was not without its drama. In January 1914, a shootout broke out between two rival gangs, resulting in the death of an innocent bystander. The hall also became a hotspot for labor struggles, with union workers seeking compensation in 1916. In another notorious incident that same year, vice squad detectives were arrested for taking payoffs from “disorderly resorts” using Arlington Hall as a front.

The hall became a focal point for anti-draft protests in 1917, where riots broke out as soldiers attempted to arrest draft dodgers. The police were overwhelmed by the large crowd, but Roosevelt’s earlier influence could be seen in the tense atmosphere.

By 1920, the Polish National Home purchased the property and Arlington Hall was closed. The building housed Polish businesses and organizations, and later became home to a popular restaurant known as The Dom. In the 1960s, Stanley Tolkin ran Stanley’s Bar downstairs, which featured bands like The Fugs, while the upstairs was rented for psychedelic light shows. In 1966, Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey transformed the upstairs space into The Dom nightclub, with The Velvet Underground as the house band. The venue later became Electric Circus, a legendary psychedelic nightclub that hosted major acts like Jimi Hendrix, The Grateful Dead, and Jefferson Airplane.

By the early 1970s, as the psychedelic movement waned, Electric Circus closed. The building was later repurposed as the All-Craft Center, a community space that operated until 2003, when it was finally renovated.

24 St. Marks Place

This building housed offices of the Children’s Aid Society in the 19th century. Founded in 1853 by Charles Loring Brace, the Children’s Aid Society was a groundbreaking organization dedicated to addressing the dire conditions faced by New York City’s abandoned, abused, and orphaned children. Its first location was on 9th Street and Avenue B, across from St. Brigid’s Church. Between 1853 and 1929, the society organized the relocation of over 150,000 children through its Orphan Train program, sending them to live with families in rural areas across the country in an effort to provide them with stable homes and opportunities for a better future.

The Children’s Aid Society was multifaceted, offering a variety of services to improve the lives of impoverished children. These included industrial schools to teach trades, lodging houses for homeless youth, and free medical care. During the harsh winter of 1875, its five Manhattan lodging houses provided shelter to 68,982 needy individuals and served approximately 277,200 meals, showcasing the immense scale of its operations. The organization also pioneered modern approaches to social work and foster care, leaving a lasting impact on child welfare in the United States.

Today, the legacy of the Children’s Aid Society, now called Children’s Aid, continues through its extensive programs supporting children and families in New York City.

27 St. Marks Place

This building served as the Girls’ Lodging House of the Children’s Aid Society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Designed to provide safe shelter for homeless or at-risk young girls, the Girls’ Lodging House was part of the organization’s broader mission to rescue children from the harsh conditions of New York City’s streets and slums. The facility offered not only beds and meals but also training in domestic skills, aiming to prepare the girls for employment or placement with foster families.

The Girls’ Lodging House became a place of joy and community during the holiday season. Each Christmas, the staff organized special dinners complete with live entertainment, treats, and a visit from Santa Claus. The highlight of the evening was Santa’s presentation of gifts, which often included essential items like warm clothing and shoes—practical yet meaningful for children who had very little.

The Girls’ Lodging House also witnessed moments of heartbreak, such as the story of 16-year-old Lizzie Glennon in 1899. Desperate to reunite with her two younger siblings, who had been placed in the lodge after their widowed father’s death, Lizzie gained entry by pretending to be in need of aid. Though she found her brother and sister, the reunion was short-lived; staff intervened before they could leave together. Lizzie’s aunt later took the case to court, but the court ultimately ruled in favor of the Children’s Aid Society. The siblings were sent westward to live with a foster family, in keeping with the organization’s practice of relocating children through the Orphan Train program to give them a chance at a better life.

The Girls’ Lodging House exemplified both the compassion and the complexities of the Children’s Aid Society’s work. While it provided essential resources and new opportunities, it also faced criticism for its sometimes rigid methods, including the separation of families. Nonetheless, the society’s efforts laid the foundation for modern child welfare systems and brought attention to the urgent need to address poverty and neglect among children.

28 St. Marks Place

This building has a colorful history, serving a variety of purposes over the decades. As early as 1897, it was at least partly used as a lodging house. An advertisement in the Brooklyn Eagle on May 5, 1902, promoted “a neatly furnished front hall room; all improvements; either lady or gentleman,” highlighting its use as affordable housing.

By 1930, the building became home to a cheap lodging house and greasy-spoon diner called The Tub, owned by Urbain Ledoux, better known as “Zero.” A charismatic and eccentric figure, Zero was dedicated to aiding the growing homeless population in the area during the Great Depression. At The Tub, he offered 5-cent meals and 25-cent lodging to the needy, providing a lifeline to many in the Bowery and Lower East Side.

In April 1930, Zero hosted an open house at The Tub to celebrate Easter, drawing over 5,000 “jobless men from the Bowery,” according to reports. They were served a hearty meal of “mulligan stew, pie, and coffee.” Despite his generosity, Zero faced numerous challenges. The Tub appears to have operated at multiple locations during this period, often struggling to stay open. The establishment was evicted from 17 St. Marks Place in 1924 due to non-payment of rent, and another location at 12 St. Marks Place was shut down by the Board of Health in 1928.

The building underwent renovations in 1962, marking a shift from its earlier uses. From 1967 to 1971, the storefront was occupied by Underground Uplift Unlimited (UUU), a head shop that became a cultural icon of the 1960s counterculture movement. UUU was known for its bold political and social activism, producing and selling iconic buttons and posters with slogans like “Make Love, Not War” and “More Deviation, Less Population.” It became the largest seller of protest pins in the country, offering hundreds of designs for 25 cents each. Today, these pins are highly collectible, with some valued at hundreds of dollars.

29 St. Marks Place

This historic building has been home to a diverse array of individuals and organizations, reflecting the changing character of the Lower East Side over time.

In 1836, it was the residence of Joseph Addison Saxton, a New York University and Yale Seminary graduate and ordained minister. Saxton later served as pastor at Presbyterian churches in Hartford, Connecticut, and South Haven, Long Island.

From 1856 to 1859, the building hosted the Harmonie Club, a German-Jewish singing society that became a cultural hub for its members. By the late 19th century, 29 St. Marks Place had likely transitioned into a boarding or lodging house, as evidenced by numerous colorful and tragic incidents involving its residents:

- 1883: Emily L. Fuller, a resident, tragically jumped to her death from a steamboat.

- 1885: Another resident, William H. Davenport, committed suicide in a New Jersey hotel room.

- 1897: Joseph Cobi, also a resident, was arrested after attempting to rob James O’Connor in Washington Square Park. Unfortunately for Cobi, O’Connor was an off-duty police officer who quickly thwarted the robbery.

In the 1930s, the building served as office space for Polish organizations and businesses, reflecting the area’s then-flourishing immigrant communities.

On April 20, 1937, the building became the site of a poignant event when Jacob Silbert, a popular Yiddish theater actor and singer, suffered a fatal heart attack while dining at a restaurant located there. Silbert, who was 67 years old at the time, had a storied career in the local Yiddish theater circuit. He co-wrote Sold to Shame, recorded numerous singles, and even had a brief moment in Hollywood with a small role as a bodyguard in the 1915 film The Winged Idol.

30 St. Marks Place

This building has witnessed both scandal and countercultural revolution, with a history as colorful as the neighborhood itself.

In 1910, resident Simon Calev was arrested for peddling “obscene postal cards and pictures,” a crime emblematic of the evolving social mores and tensions of the early 20th century.

By 1967, 30 St. Marks Place became home to one of the most iconic figures of the American counterculture, Abbie Hoffman. Living there with his wife, Anita Kushner, Hoffman launched the Youth International Party (Yippies) from this very building. Dissatisfied with what he viewed as the overly passive nature of the Hippie movement, Hoffman sought to inject more provocative and confrontational energy into activism. The Yippies were known for their theatrical, disruptive stunts aimed at drawing attention to social and political issues.

One of Hoffman’s memorable local stunts involved planting a tree at the corner of Third Avenue and St. Marks Place—then a cobblestone street—which caused a traffic jam that lasted for hours. Another famous act took place at the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), where Hoffman threw $1,000 in $1 bills onto the trading floor. The chaos that ensued, as traders scrambled to grab the cash, led the NYSE to significantly tighten its security protocols.

Hoffman’s activism wasn’t limited to stunts. He played a central role in the protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, which culminated in his trial as part of the Chicago 7. Charged with inciting a riot, Hoffman used the trial as a platform for his ideas, turning the courtroom into a stage for his unorthodox tactics and wit. Though he was initially convicted, the verdict was later overturned on appeal.

Hoffman went on to write several influential books, including Steal This Book and Revolution for the Hell of It, which became manifestos for the counterculture movement. He also made a cultural cameo in the movie Forrest Gump, portrayed in the scene at the Washington Monument where he delivers an impassioned anti-war speech.

Anita Kushner was a Yippie activist, writer, and prankster, and a key collaborator in some of the most memorable pranks of the Yippie movement. She supported Hoffman during his years living underground, all while raising their son, America. Their correspondence from April 1974 to March 1975, written while Hoffman evaded a prison sentence for allegedly selling cocaine, was compiled and published in 1976 as To America with Love: Letters from the Underground. Kushner also authored the novel Trashing under a pseudonym.

In one of her boldest acts, she traveled to Algeria to meet Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, aiming to forge a coalition between the Panthers and the Yippies. Kushner’s life and activism were dramatized in the 2000 film Steal This Movie, where she was portrayed by Janeane Garofalo. She passed away from breast cancer on December 27, 1998, at the age of 56.

Abbie Hoffman’s life came to a tragic and controversial end in 1989 when he died from an overdose. While officially ruled a suicide, conspiracy theories have linked his death to covert operations and political figures, including former President George H.W. Bush, reflecting Hoffman’s polarizing legacy.

31 St. Marks Place

This building has a rich and dramatic history that includes tales of deception, hospitality, and survival.

On June 11, 1858, the New York Times published a “warning to housekeepers,” describing a German man, about 21 or 22 years old with a clean-shaven face, who was deceiving residents in the area. This conman would gain entry to homes by preying on housekeepers or women alone during the day. In one notable incident, he convinced a housewife living at 31 St. Marks Place that her husband had sent him to repair broken furniture. Once inside, he demanded money, but the woman raised an alarm, and the intruder fled before he could commit a robbery.

By 1862, the building had taken on a more domestic role, with an advertisement in a local newspaper offering “neatly furnished rooms” with “board and the comfort of home,” reflecting its use as a boarding house.

A dramatic chapter unfolded on a sweltering night in June 1897, when a large fire broke out at 31 St. Marks Place, nearly claiming the lives of the building’s 18 families. The fire began on the first floor and quickly spread through the stairwell, reaching the top floors. The situation was chaotic, with some residents overcome by smoke and flames while others scrambled to safety. Firefighters from Hook & Ladder No. 3 heroically rescued many, using ladders to reach those trapped at windows. Others managed to escape via fire escapes. Thanks to these efforts, all residents survived the blaze, though the building itself suffered significant damage.

33 St. Marks Place

In 1889, boarder Martin J. Flynn, a resident here, became embroiled in a botched Midtown robbery attempt. Flynn was fatally injured after being stabbed in the eye with an umbrella and suffering a fractured skull during a confrontation with his intended victim and bystanders. After spending five nights untreated in a jail cell and enduring misdiagnoses from city doctors, he succumbed to his injuries at his home, sparking public criticism of New York City’s inadequate healthcare system.

In 1901, Morris Bernard lived here with his brother George, who ran a ladies’ tailor shop on the ground floor. Morris tragically died after stepping off a train in Brooklyn that had overshot the platform. He fell into the street and succumbed to his injuries hours later.

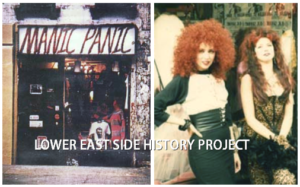

Fast forward to the 1980s, when the building housed Manic Panic, a pioneering punk-rock boutique founded by Bronx-born sisters Tish and Snooky Bellomo. Former backup singers for Blondie, Tish and Snooky opened the store in 1977, making it one of the first punk shops in America. Located at the heart of the burgeoning East Village punk scene, Manic Panic became synonymous with bold self-expression, offering wild fashion, accessories, and their signature line of vibrant hair dyes.

The sisters’ neon hair colors and unconventional makeup revolutionized alternative beauty and became cultural touchstones for rockers, goths, and rebels worldwide. Despite starting with limited resources, Tish and Snooky turned Manic Panic into a global brand, with their products still popular today. The store’s legacy as a haven for individuality and creativity remains an integral part of East Village history.

In 1989, 33 St. Marks Place gained cinematic fame when it appeared in Ghostbusters II as the location of Ray’s Occult Books, owned by Dan Aykroyd’s character, Ray Stantz. The quirky bookstore, specializing in paranormal literature, perfectly matched the eclectic and otherworldly spirit of the area. While the building’s exterior has changed over time—white paint removed from its brick facade and a staircase added—it remains a cultural landmark for both film and punk history enthusiasts.

34 St. Marks Place

This location has served many roles over the years, from medical offices to a creative hub for one of the most vibrant bands of the 1990s.

In the 1860s, it was home to the offices of Dr. Lighthill, a renowned throat and lung specialist. Dr. Lighthill gained fame for his work on hearing restoration, authoring the well-regarded A Popular Treatise on Deafness, Its Causes and Preventions. Testimonials from his patients described miraculous recoveries, such as one man whose hearing was restored after 10 years of complete deafness. His reputation extended beyond New York, with notable operations in Hartford, Connecticut, and advertisements in major newspapers, though his services were not inexpensive—consultation letters had to include $5 to be acknowledged.

By 1898, the property changed hands when August Ruff sold the six-story tenement building to Max Clausen.

Fast forward to the 1990s, when 34 St. Marks Place became the home of the groundbreaking musical trio Deee-Lite. The band, composed of vocalist Lady Miss Kier (Kierin Kirby), DJ Dmitry Brill, and DJ Towa Tei, formed in 1986. The members came from diverse backgrounds—Lady Miss Kier hailed from Youngstown, Ohio, and initially moved to New York City to study fashion design. Dmitry, originally from Ukraine, and Towa Tei, a Japanese-born DJ, met Kier in the city’s thriving downtown club scene, where they bonded over their shared love of funk, house, and psychedelic music.

Living and working in the East Village, the group fused their eclectic influences into a distinctive sound and aesthetic. Their debut single, Groove Is in the Heart, became an international sensation in 1990, topping charts and earning critical acclaim for its infectious beat and colorful music video. The track featured legendary bassist Bootsy Collins and rapper Q-Tip, solidifying its place as a dance anthem of the era.

131 2nd Avenue/ St. Marks Place

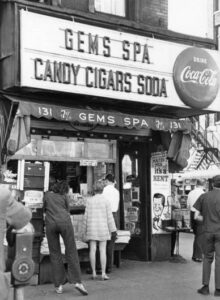

In 1922, the storefront housed the Chain Shirt Shop retail outlet, but by the early 1950s, Gems Spa (later Gem Spa) had established itself as a cornerstone of the community. It became famous for its egg creams, a classic New York drink. The store originally made its own brand of syrup in the basement, ensuring the freshest, most authentic egg creams served at its long diner-style counter with swiveling stools.

Gem Spa quickly gained a reputation as a hangout for locals, artists, and intellectuals. In the 1950s, beat poet Allen Ginsberg dubbed it “an oasis in the middle of the jungle,” referencing its 24-hour availability of coffee, magazines, and conversation at a time when such spaces were rare. The store carried publications from around the world, drawing in those eager to discuss current events and exchange ideas.

By the 1960s, Gem Spa had become a destination for counterculture icons and teenage runaways arriving in New York City. A 1968 New York Times article highlighted the store’s role as a gathering place for young adventurers beginning their East Village journeys.

In 1973, Gem Spa secured its place in pop culture history when the New York Dolls posed in front of it for the back cover of their debut album. The now-iconic shot, captured by Vogue photographer Toshi with a modest $900 budget for hair, makeup, and photography, helped immortalize the store as a symbol of East Village cool.

Through the years, Gem Spa adapted to changing times but always stayed true to its roots. While the diner-style counter eventually disappeared, the store continued to serve authentic egg creams, made from one of its two remaining vintage soda fountains, until it closed its doors in 2020.

48 St. Marks Place

This building is currently home to Iglesia Metodista Unida Todas Las Naciones (Church of All Nations), which originated in 1904 with meetings at the Wesley Rescue Hall on Houston St. & 2nd Ave. In 1975, the church moved to this location after an attempt by a local gang to take over the Wesley Hall building.

Originally, the building housed the First German Methodist Episcopal Church, as indicated by the name carved into the facade. The church, founded in the 1840s, originally occupied a building at 254 E. 2nd St, but by the end of the century, it relocated here to expand its presence in the community.

In May 1893, the church petitioned New York State Governor Roswell Pettibone Flower for funds to purchase a 25-acre plot of land in Newton, NY, with the intention of establishing a cemetery. However, the request was vetoed. Governor Flower cited local opposition, noting that the citizens of Newton were concerned there were already too many cemeteries in the town, with the number of graves surpassing the living population.

In 1931, the church faced a financial scandal when John H. Bachmeier, the church treasurer, was arrested for embezzling $60,000. An audit uncovered the missing funds, leading to Bachmeier’s arrest and the church’s subsequent public scandal.

51 St. Marks Place

In 1866, a somewhat-notable event took place at this address when housemaid Kate Roberts was arrested for stealing from her employer, Eliza Newcombe, a resident of this home. Roberts was accused of taking a $30 black lace veil while working for Newcombe and was held on a significant bail of $2,000 for the theft.

By the early 1980s, the building had transformed from a residential space to an influential contemporary art gallery known as 51X. This gallery became a key venue in the rise of Urban Contemporary Art, also known as Graffiti Art, during a pivotal time for the New York City art scene. 51X showcased works by several prominent figures in the Street Art movement, including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and even Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols. These artists, known for their rebellious spirit and bold visual statements, used public spaces and galleries alike to challenge traditional notions of art and culture.

51X played a critical role in reintroducing New York City as a global powerhouse in the contemporary art world, marking a return to influence that had not been seen since the era of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s and ’50s, when artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning honed their craft in the East Village. Much like the Abstract Expressionists, the graffiti artists of the 1980s used their work to convey personal expression, political messages, and social commentary, but with a distinctive urban edge that reflected the gritty streets of New York.

The gallery’s exhibitions showcased the cross-pollination between street culture and the art world, with Basquiat’s raw, often chaotic paintings and Haring’s bold, graphic images breaking down the barriers between fine art and street art. This period also saw a fusion of pop culture and punk, as Johnny Rotten’s involvement in the gallery highlighted the intersection of music, fashion, and visual art in a transformative cultural moment.

51X was more than just a gallery; it became a cultural hub, where artists, musicians, and intellectuals came together to shape the creative output of a generation, helping to propel the East Village into its status as the epicenter of the artistic counterculture in New York City during the 1980s. Its influence on the graffiti art movement and its role in bridging the gap between street art and the traditional gallery system helped to redefine the boundaries of contemporary art in America.

52 St. Marks Place

This building was once home to the Hebrew National Orphan Home, a children’s care facility that served Jewish children in need for nearly half a century. The orphanage was an important institution in New York City, providing care, shelter, and education to children who had lost their parents or were otherwise in need of support.

In September 1919, the orphanage, along with its 100-member committee, launched a major fund drive to raise $500,000 to care for over 500 children. To kick off the campaign, they held a dinner at the prestigious Astor Hotel and established a campaign headquarters at 1 2nd Ave. They appealed to both Orthodox and Reformed Jews, issuing a public statement that underscored the urgent needs of Jewish philanthropic efforts at the time. The statement highlighted the fact that many non-Jewish organizations were caring for Jewish children, but were unable to meet the overwhelming demand, with many children being turned away due to a lack of funding.

The success of this campaign was evident when, on June 19, 1920, the orphanage opened a new, state-of-the-art facility in Westchester, NY. The $750,000, 20-acre facility included amenities like a gymnasium, library, synagogue, dining hall, and dormitories for up to 400 children. This new home was a symbol of the Jewish community’s commitment to providing for its own, ensuring that children in need would have a safe and nurturing environment in which to grow and learn.

The orphanage’s influence extended beyond its walls, as evidenced in February 1928 when more than 2,000 Jewish residents from the Lower East Side marched in a parade to honor the 13th anniversary of the Zionist movement. Among those marching were a small group of boys from the orphanage, who participated in the event. This parade was part of the larger NYC Zionist Parade, an annual event that celebrated the growing political strength of the Jewish community in New York. The Zionist movement, which sought to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine, was gaining momentum during this time, and events like the parade played a role in building public awareness of its efforts.

57 St. Marks Place

By the 1920s, the building became home to a social club known as The Mansion, a hub for social gatherings.

One significant event held at The Mansion occurred on July 28, 1925, when over 250 members of the Combined Peddlers’ Association of New York paid $5 a plate to attend a dinner in honor of Morris Loopesko, who was dubbed the “King of the Peddlers.” Loopesko was a prominent figure in the peddling business and this dinner was a tribute to his success.

The building was also the site of a tragic event on June 15, 1935, when a fire broke out during a wedding ceremony. The fire, which started in the canopy above the bride, spread quickly through the hall, killing at least 7 people and injuring over 40 others. More than 250 guests fled for their lives, and the bride and groom, Pearl Sokolower and Louis S. Shein, had to reschedule their wedding for later that year, though they did eventually marry in August 1935 at another location.

By the mid-20th century, the building was home to the Holy Cross Polish National Catholic Church, where Reverend Rene Zawistowski served as pastor until his death from cancer in 1968.

In the 1980s, however, the building became an iconic location for the New York City’s underground and punk scenes, housing Club 57, one of the most famous and influential venues in the city’s counterculture movement. Club 57 was managed by Anne Magnuson and quickly became a hub for art, music, and creative expression, embodying the DIY, anti-pop culture aesthetic of the era. The venue was a space for experimental, interactive, and immersive experiences, including Day-Glo art shows, punk rock performances, and extravagant theme parties.

The club was a magnet for up-and-coming artists and performers, and it became a launchpad for many avant-garde figures. Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Kenny Scharf, among others, showcased their groundbreaking artwork here. The club’s visual culture reflected the vibrant street art scene, with its fluorescent murals and graffiti-inspired installations. Fleshtones, Klaus Nomi, Joey Arias, and Lypsinka were just some of the live performers who graced the stage, embodying the era’s exuberant, eclectic energy.

Club 57 was also notable for attracting performers from diverse genres. Fab 5 Freddy, a leading figure in the hip hop scene, made his mark here, while Wendy Wild and John Sex brought their punk sensibilities to the stage. The club was central to the creative community that defined New York’s East Village during the early 1980s, often acting as a safe space for experimentation and non-conformity in both art and music.

58 St. Marks Place

This building was once home to the Ladies’ Hebrew Lying-In Society, a vital charitable institution founded by the United Hebrew Charities organization. Established to aid expecting mothers, the Society also provided valuable education to women and children in trades such as sewing, cooking, and shoe-making. The Lying-In Society served as both a refuge and a resource for families in need, and it became an important community institution in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Every Thanksgiving, the facility hosted up to 300 neighborhood children for a traditional holiday dinner, a special event that helped build a sense of community and support for families during the holiday season. The Society was established with the mission of providing relief to the most vulnerable members of society, and this building was purchased by the Lying-In Society in 1880 for $17,000.

In 1880, the young girls involved with the Society sewed 841 dresses, which were distributed throughout the community, alongside 1,495 pairs of shoes and 480 quilts. They also provided “several hundred yards of flannel.” Additionally, the organization assisted with burials for 40 adults and 147 children, offering free transport for 204 people to Europe and abroad.

The scope of the Society’s work was vast. In 1885, 11,831 people were aided through its various programs. That year alone, 636 tons of coal were distributed to those in need, 1,027 home visits were made by charity doctors, and 2,252 prescriptions were written. The total expenditures for the year amounted to $58,627.50, but the organization managed to remain financially stable, with a balance of $1,626.13 in the black.

In Summer of 1893, the superintendent of United Hebrew Charities, Charles Frank, died, and a memorial service was held at the building, presided over by the organization’s president, Henry Rice. In 1895, The New York Times published a two-page article praising the efforts of United Hebrew Charities, calling it “No other institution in the world deals with such a variety of philanthropy,” underscoring the breadth and impact of its charitable work in the community.

60 St. Marks Place

On Sunday, March 21, 1872, members of the 55th Regiment of the National Guard gathered at this address before providing a funeral escort for Colonel Eugene Le Gal, an ex-commander of the regiment, who had passed away from natural causes after retirement.

In 1891, Simon Strauss, a resident of this building, tragically lost his life when he and another individual were run over by a 2nd Avenue streetcar.

In June 1895, the building’s owner, Joseph Krieger, a bondsman, was ordered to testify in court along with several other bondsmen. They were linked to a scheme in which saloon owners allegedly scammed the city by applying for and receiving multiple bonds, sometimes on properties they did not even own.

Between 1951 and 1957, Joan Mitchell, a pioneering figure in the American Abstract Expressionist movement, lived in this building and created some of her most experimental work. Born in Chicago in 1925, Mitchell was considered part of the second wave of Abstract Expressionists, along with contemporaries such as Lee Krasner, Grace Hartigan, and Helen Frankenthaler. Mitchell moved to New York City in 1949, where she studied briefly at Columbia University before becoming a student of the influential German-born painter Hans Hofmann. Under his guidance, she honed her skills and developed a unique style that combined emotional depth with abstract forms.

Mitchell’s work was recognized for its expansive, multi-canvas landscapes, energetic brushstrokes, and splashes of vibrant color. Her paintings often conveyed intense emotions, ranging from deep sadness to rage, and were characterized by their raw, visceral expression. One of her signature techniques was creating large, sprawling canvases that allowed her to engage with the entire surface, drawing the viewer into the intensity of her experience. This period in Mitchell’s life in the East Village was formative, as she explored new forms of abstraction and painted some of her most powerful and influential works.

62 St. Marks Place

The Church of St. Cyril is a key religious and cultural institution for the Slovenian-American community in New York City. Founded in 1908, this church serves as a spiritual and cultural center for the city’s Slovenians, who primarily settled in neighborhoods like the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village at the turn of the 20th century. The church continues to operate as a vibrant center for Slovenian heritage, hosting cultural events, religious services, and community gatherings.

The church is also home to the Slovenian Cultural Center, which has been instrumental in preserving the traditions, customs, and language of Slovenian immigrants. The center hosts a range of cultural activities, including language classes, folk dancing, music performances, and events that celebrate Slovenian holidays and customs. The building itself, which has served the community for over a century, stands as a symbol of the resilience and close-knit nature of the Slovenian-American population in New York.

The Slovenian community in New York City dates back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when waves of immigrants arrived from what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which included present-day Slovenia. By the early 1900s, a significant number of Slovenian immigrants settled in New York, particularly in the Lower East Side and surrounding neighborhoods. Many were working-class individuals who found employment in the city’s factories, docks, and service industries.

The community’s religious life was centered around the Catholic faith, which was brought with them from Slovenia. The establishment of St. Cyril’s Church was a direct response to the growing Slovenian population in the city, providing a place of worship and a sense of community for immigrants who were far from home.

Over time, the Slovenian community in New York became more integrated into the broader fabric of the city’s immigrant groups. However, they maintained their cultural identity through local associations, community organizations, and, of course, St. Cyril’s Church. The church became the heart of the community, offering not only religious services but also social support, especially for newly arrived immigrants.

66 St. Marks Place

This building is the site of the St. Mark’s Hospital, incorporated on March 8, 1890. Originally founded as the Lodge & Association Hospital in 1887, it served as a medical center catering to German-American organizations in the area. The early hospital was poorly equipped, but under the leadership of Dr. Carl Beck, it became notable for its innovations, including Dr. Beck being one of the first surgeons to apply X-rays to treat fractured bones.

When the Lodge & Association Hospital fell into debt and was on the verge of closing, Dr. Beck, along with several colleagues, a lawyer, and a local merchant, took over the facility. They pledged to pay off the debts and re-incorporated it as St. Mark’s Hospital in 1890. Dr. Beck remained president of the hospital until 1910, when he became ill from the long-term effects of his work with X-rays.

St. Mark’s Hospital quickly became a haven for the sickest and most impoverished residents of the Lower East Side. The hospital became known for its policy of treating all patients, regardless of their ability to pay, which was an uncommon practice at the time. Patients were charged between 45 cents and $1 a day for boarding and treatment, but many were cared for free of charge, especially those too poor to pay. A report from 1893 revealed that the hospital treated 615 patients in-house and 454 surgeries, with a fatality rate of 10.5%—a figure that was down 2.5% from the previous year. The higher-than-average mortality rate was largely due to St. Mark’s willingness to accept patients that other hospitals had turned away as too sick or too risky to treat.

In 1893, the hospital expanded its operations, purchasing a building at 177 Avenue A for $50,000. To raise the necessary funds, St. Mark’s Hospital sold $10 bonds that were redeemable for hospital care—10 bonds could provide 4 months of hospital bed for the buyer, and 30 bonds entitled one to a year’s worth of treatment. In 1896, the hospital began to take a more political stance, producing a show at the Academy Theater titled “Cuba Free”, which aimed to raise awareness about Cuba’s struggle against Spanish rule. The play was endorsed by the Cuban Junta and the Daughters of Cuba, with Professor Emile Schoen conducting the orchestra.

In September 1898, a group of 271 soldiers suffering from malaria arrived in New York City aboard the steamship Shinnecock. These soldiers, who had been involved in the Spanish-American War, were treated at several hospitals, including St. Mark’s and St. Francis Hospital. Unfortunately, two soldiers under St. Mark’s care died from their illness. Later that year, St. Mark’s purchased the building at 179 2nd Avenue for $38,000, and by 1909, it had expanded further by purchasing 240 E. 12th Street for $20,000, which was converted into a dormitory for the St. Mark’s Training School for Nurses.

By 1915, the hospital began plans for another expansion, seeking additional funding. A letter of support from Theodore Roosevelt stated, “St. Mark’s Hospital is the only hospital in NYC where women who are victims of social evil receive ward treatment,” underscoring the institution’s unique and compassionate care for marginalized populations.

Despite the continued support, financial difficulties persisted. In December 1926, the cornerstone was laid for a new, modern 5-story, $600,000 building, but the hospital continued to struggle with mounting debt. By May 17, 1931, St. Mark’s Hospital was forced to close its doors and filed for bankruptcy, marking the end of its over 40-year service to the Lower East Side community.

68 St. Marks Place

In the late 1800s, this address served as a boarding or lodging house, a common type of residence in the area at the time. By the 20th century, it had become a more fashionable address.

In the 1930s, the chief clerk of Manhattan Traffic Court, Aaron Soldfron, lived here.

On May 17, 1939, Dr. Solomon Goldenkranz, a former Tammany Hall leader and a dominant figure in the 8th Assembly District of the Lower East Side, died here at the age of 69 after a two-month battle with illness. Goldenkranz had been a prominent member of Tammany Hall for over two decades, known for his influence within the Democratic political machine.

In 1931, Goldenkranz and other Tammany leaders were called to testify in a high-profile investigation into the NYC pier scandal. The investigation focused on allegations that Tammany Hall officials were accepting large sums of money from steamship companies in exchange for favorable leases on waterfront properties controlled by the city.

By the 1930s, Tammany Hall’s once-dominant political grip on New York City was beginning to unravel. In 1933, the newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt worked to weaken the political machine, supporting Fiorello LaGuardia, an anti-Tammany candidate, in his successful bid for mayor. Roosevelt also stripped Tammany Hall of much of its federal funding as part of his New Deal programs, further diminishing its power.

Goldenkranz was one of three major Tammany figures who suffered a political defeat in the 1935 elections, marking a significant blow to the organization’s century-long control over New York City’s political landscape.

75 St. Marks Place

The Holiday Cocktail Lounge is a classic East Village bar that has been a beloved spot for generations.

In the 1950s, celebrated poet W.H. Auden lived next door at 77 St. Marks, and it was here that he did much of his writing, often sitting at the front window of the bar. W.H. Auden, born Wystan Hugh Auden, is known for its range of themes, from political to personal, often blending both into complex and poignant reflections on modern life. He became known for his use of formal verse (influenced by earlier poets like John Donne) while also experimenting with more free verse and modernist styles. He was also noted for his deep engagement with European politics, history, and the human condition.

Auden moved to the United States in 1939, fleeing the rising fascist threat in Europe, and became a naturalized American citizen in 1946. He lived in New York City, where he was part of the vibrant intellectual and artistic scene of the 1940s and 1950s. While he continued to write poetry, Auden’s work also reflected his growing interest in the spiritual, philosophical, and religious aspects of life, particularly after he converted to Christianity in the 1940s.

His time living in the East Village was marked by his immersion in the area’s bohemian culture, and it is during this period that he wrote much of his later work, including parts of his Collected Poems.

The Beat Generation was also a regular presence at the Holiday, with Allen Ginsberg and other members of the Beatnik movement frequenting the lounge during the 1950s and early 1960s. The bar became a laid-back gathering spot for writers, poets, and artists of all stripes, who gathered there to discuss culture, politics, and art.

In the 1960s, the Holiday is rumored to be a casual haunt for Frank Sinatra when an agent of Sinatra’s supposedly lived across the street, and by the 1980s, it is said that the bar became a regular stop for Madonna, who lived just a block away. But these are similar legends to “George Washington slept here,” and should maybe be taken with a grain of salt.

The bar was opened by local legend, Stefan Lutak, who was born in Ukraine in 1920. During World War II, he served in the Soviet Army and endured the harrowing conditions of the battle of Stalingrad. Reflecting on his experiences, he shared with the NY Press, “The winter was terrible. The ice came from your mouth. We slept in the snow, with nothing to eat. Two, three, four days—sometimes a whole week—on an empty stomach. The kitchens were gone. They killed the horses, then the cooks. We ate leaves, but by November, even the leaves were gone.”

After the war, Stefan emigrated to New York City, arriving on Nov. 18, 1949, to Pier 82 on the West Side of Manhattan. According to the NY Press, “The boys from the Ukrainian Sport Club on 10th St. between Avenues A and B came to pick him up.” Mr. Lutak passed away in 2009.

77 St. Marks Place

In the early 20th century, the basement of this building was home to Sovremenny Mir (“Contemporary World”), a Russian-language, pro-Communist newspaper that played a crucial role in promoting socialist ideologies in New York City.

Lev Davidovich Bronstein, better known as Leon Trotsky, worked for the publication during his time in New York in 1917. Trotsky was a central figure in the Russian Revolution and one of the most iconic revolutionaries of the 20th century. As second-in-command to Vladimir Lenin, he helped lead the Bolshevik forces to victory in the October Revolution and was the founder of the Red Army, which played a key role in the Russian Civil War.

Trotsky’s presence in New York during the tumultuous period of 1917 was part of a broader wave of radical intellectuals and activists who were drawn to the city’s burgeoning socialist movements. New York was a magnet for left-wing political thought in the early 20th century, especially among immigrant communities, and it became a major center for Communist and anarchist activism. The Russian émigré population in particular had a strong influence on the political landscape, and Trotsky’s writings and speeches during this time helped to spread revolutionary ideals in the United States.

Trotsky left New York for Mexico after a failed attempt to overthrow Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union, as part of a broader ideological split with Stalin over the future direction of communism. After his expulsion from the USSR, Trotsky lived in exile and continued to advocate for permanent revolution against Stalin’s increasingly authoritarian regime. His writings on Marxism and his critique of Stalinism were highly influential, shaping global communist movements.

In 1940, while in Mexico, Trotsky was assassinated by a Soviet agent, marking the tragic end to the life of one of the most pivotal figures of the Russian Revolution and a key figure in the history of communism. Despite his death, Trotsky’s legacy continues to resonate in socialist and Marxist thought worldwide.

80 St. Marks Place

In the 1860s, this address was home to Mr. George W. Thompson’s gas fitter shop. In November 1860, Thompson filed a complaint at the Tombs prison against his employee, Charles Webber, a German immigrant, accusing him of stealing 500 unfinished gas burners and tools worth $250. Webber was arrested and held for trial.

By the 1930s, the building was home to Walter Scheib Bar & Grill.

In the 1960s, the space became Theater 80, which produced dance performances, ballets, and musicals. In 1967, it was the venue for the premiere of You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown. By the 1970s and early ’80s, it operated as a movie theater, and it became the home of the Pearl Theater Company in 1986.

Outside the theater, on the sidewalk, is a mini-Off-Broadway Walk of Fame. The handprints, footprints, and signatures of some of the 20th century’s most notable actors and actresses, including Joan Crawford, Gloria Swanson, Myrna Loy, Kitty Carlisle, and Dom DeLuise, are etched in cement. (DeLuise, it seems, had connections to the Rat Pack—he shared an agent who lived next door, which may explain some of his pull.)

In 1999, there was a small push to remove the memorial when a Department of Transportation inspector deemed the sidewalk “unsafe,” citing concerns that “people might trip.” Fortunately, the Department of Buildings ignored the complaint, and the sidewalk remains intact to this day.

The theater recently closed and the building went into foreclosure. It is being gut renovated at the time of this publication.

93 St. Marks Place

In 1858, a woman named Mrs. Schrimer lived at this address. She hosted at least one boarder, Samuel Morris, who was arrested for stealing garments from her and giving them to one of his two wives. He was charged with bigamy when authorities uncovered his secret marriages.

In 1864, the building was home to Carl Hecker, a well-known and respected, German-born artist. Hecker was an influential teacher and the founder of the Hecker School of Art, which trained thousands of artists in the 19th century. He was beloved by his students and recruited in 1877 to teach “photo color & photo crayon” at Cooper Union.

In 1868, Eliza F. Dodge, an 80-year-old resident, died here.

In December 1884, boarder Herman Russ was arrested and tried for stealing hundreds of dollars worth of furs from his employer on Broadway. He was caught with seal, beaver, and otter pelts in his possession.

During the 1890s, the building served as the meeting place for the Hungarian Literary Society. On Christmas Eve in 1898, the society distributed warm clothes to 300 local children and allowed them to choose a small anonymous gift from under the tree. These gifts were also distributed throughout the tenements with “no distinction between race, creed, or nationality.”

Today, the building is home to Little Missionary’s Day Nursery, which has served the community since 1901. It is the oldest continuously operating non-sectarian school in NYC. The nursery was founded in 1896 by Miss Sara Curry, who earned the nickname “Little Missionary” through her work in the Lower East Side. Curry dedicated her life to providing affordable childcare for low-income, working-class families.

In 1901, the building was purchased with funds raised through donations from generous benefactors. Curry organized cooking, sewing, and childcare classes for mothers, and encouraged fathers to seek counseling for “sobriety & responsibility.”

In the 1930s, the Missionary hosted annual fundraisers at prestigious venues such as the Carlyle and Washington Hotels. These events included dances, dinners, and fashion shows, which helped raise money for the nursery’s expansion. By the 1940s, the organization had an annex in New Jersey, which later moved to Rye, NY.

Sara Curry retired in 1939 and passed away in 1940 at the age of 77. Her daughter, Anna Almasy, took over the school and ran it for 30 years until her own retirement in 1973.

94 St. Marks Place

By the turn of the 20th century, the building housed Grassman & Hirtz Real Estate Co., owned by the reportedly eccentric Russian immigrant C. C. W. Grassman. Grassman was a beloved figure among the neighborhood children. Known for his thick accent, large belly, white hair and mustache, and signature Russian sailor’s cap, he earned the nickname “Summer Santa Claus” for his generosity. He handed out candy and coins, allowed children to play in the building’s hallways, and even paid organ grinders to entertain them outside his office.

Parents, however, viewed him with suspicion. Grassman’s eccentricities and rumored Communist ties led many to warn their children about the “terrible man.” Grassman did little to dispel the rumors when, in 1904, he placed a peculiar international advertisement:

“Wanted, steamers of not less than 6,000 tonnage, to have speed of not less than 18 knots & more, & must be made so they can be fitted with armor plate… Apply to Grassman & Hirtz Co, 94 St. Marks Place.”

This sparked gossip throughout the community that Grassman was building his own navy. When reporters confronted him, Grassman admitted he was brokering ships for an unidentified country in need of naval vessels. He claimed to have already bought and sold five ships and was aiming to acquire as many as 200. His activities added to his mystique and the air of unease surrounding him.

Today, the building houses Fun City Tattoo & Cappuccino, a unique establishment steeped in history. Fun City Tattoo is celebrated as the oldest operating tattoo parlor in New York City, dating back to 1976. It played a significant role in the city’s tattooing renaissance, particularly during the period when tattooing was illegal.

Jonathan Shaw, a legendary tattoo artist, operated a private studio here during the tattoo ban, which lasted from 1961 to 1997. The ban was imposed after an outbreak of Hepatitis C was linked to tattoo parlors, primarily in Chinatown. Despite the prohibition, Shaw’s work and Fun City Tattoo kept the art form alive and helped establish New York as a hub for world-class tattoo artistry.

Today, the East Village continues to be home to some of the most skilled tattoo artists in the country, including icons like the world-famous Paul Booth, further cementing the area’s legacy in tattoo culture.

98 St. Marks Place