Jim Power, commonly known to locals as ‘the Mosaic Man,’ is a former Vietnam veteran who set out to make the East Village an arts destination by creating a set of 80 mosaic-decorated light posts. Each lamp post has its own theme, with designs inspired by significant events in history and culture that took place in those areas. The light post are covered in a myriad of glass pieces and ceramic fragments. Each work is comprised between 1,000 and 2,800 small tiles.

In the late 1980s and early 90s the City of New York created a campaign entitled ‘City’s Anti-Graffiti Task Force.’ The goal of the program was to provide a higher quality of life, unfortunately that meant 50 of Jim’s beautifully-adorned artworks were removed. Throughout the years Mr. Power managed to rebuild every one of them.

Local Villagers banded together to ensure that the artistic legacy of Jim Power remained intact. In 2004 City Lore, an organization that supports New York’s cultural heritage, honored Power in it’s People’s Hall of Fame. Tours are available to highlight Power’s work in the Lower East Side. ‘Mosaic Trail of East Village,’ spans from Broadway and Eighth Street to East Tenth Street and Avenue B. Jim Powers living conditions became less than secure in 2003 when he moved into a squat called ‘The Cave’ at 120 St. Mark’s Place. In 2006, The Cave, where many artist lived, was gutted.

The history of squatting is instrumental in understanding the culture and resilience of the Lower East Side. Much like Jim Power’s mosaic streetlights, squats may appear at odds with the quickly developing Lower East Side. Both are relics from another time that the City Government would happily demolish, but with help from a supportive community, both the squats and the mosaics have found a found a place for themselves on the lower east side.

The squats remain affordable housing in an overly gentrified neighborhood. The Cave started out like many squat houses in the Lower East Side back then, entire blocks consisted of rubble and empty, decaying buildings that had fallen into the ownership of the city. Drug users lined up on sidewalks and buildings sometimes burned all night. In the 1960s and 70s neighborhoods in the Lower East Side ended up largely depopulated, leaving a slew of abandoned buildings.

These buildings became property of the city, but in the 70’s and 80’s many students, and homeless moved in. The squatters initially didn’t face much resistance from the city, even though they were illegally occupying city owned buildings. Like the 1862 Homestead Act which, stated that farmers moving westward needed to make improvements, and farm it for a minimum of five years to gain ownership of the land, squatters began repairing the abandoned buildings

They set up running water and rebuilt staircases. Squats were the true meaning of community. City officials saw them as little more than criminal trespassers. When faced with eviction they learned how to build barricades and attempts to evict Lower East Side squatters from the late ‘80s on brought escalated police and squatter tactics. Bullet Space, a former squat and one of the first to be turned over to its residents is located on 92 East Third street has always and continues to be an artist collective and gallery. A notable squat, Umbrella House located on 21-23 Avenue C and its residents have recently transformed the space into a rooftop garden, which provides food to locals in the neighborhood.

Squatters rights however, which refer to a specific form of adverse possession, state that after 30 days a squatters has the right continue living in the building, until the owner goes through a process of legal eviction. Adverse possession allows for real estate to change ownership without payment if someone occupies the property continually for ten years. In the mid-to-late 90s the squatters and the police squared off. One particularly memorable event came in 1995 when officers equipped with helmets, shields and an armored vehicle expelled squatters from two tenements on East 13th Street.

By the end of 90’s a secret negotiation began between the city and the squatters to legalize the squatters’ buildings. As part of the agreement, the tenements the squatters occupied had to be brought up to code. Through former Mayor Rudy Giuliani, the city would sell the squatters buildings to a third party, non-profit organization called the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB). UHAB was born in the midst of New York City’s economic crisis of the 1970s. and became a voice for the squatters by creating strong tenant associations and lasting affordable co-ops.

In 2002, the government of New York City granted provisional ownership of 11 squats to its tenants; each building was sold for one dollar. Jim Powers mosaics were removed then put back because of community support. Squats were facing a similar peril, their resilience pressured the city to make a deal. Now these spaces stand as cultural landmarks and represent the ethos of the community.

At a famous, former squat called ‘C-squat’ located at 155 Avenue C between Ninth and Tenth street, the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space (MoRUS) opened in 2012. The goal is to archive the history of grassroots actions, while also serving as an educational center for the East Village community’s rich and culturally diverse history. On June 24th, MoRUS is giving a tour of Community Gardens throughout the Lower East Side entitled ‘Grow Me A Garden: Seeding a Community Garden District in NYC.’ More information can be found on their website: http://www.morusnyc.org/.

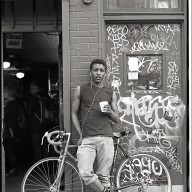

A local New Yorker and artist currently studying at the The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Technology.