Summary

Between 1880 and 1920, over 4 million Italians immigrated to the United States, fleeing poverty, political instability, and natural disasters in their homeland. Many arrived with dreams of economic opportunity, only to encounter a hostile society that marginalized them as racially inferior, religiously suspect, and culturally unassimilable. This article examines the systemic exploitation of Italian immigrants through the padrone system and the wave of lynchings that targeted them between the 1870s and 1920s.

I have been doing lectures, giving tours, and teaching classes at universities for over two decades, and to my disappointment, 90% of people I teach—including Italian Americans—never learned the true, dark history of how many our ancestors arrived to the United States. It is just not taught in schools, and somehow, History Channel and the like conveniently avoid the topic. When I ask Italian Americans what they think, most say something like, “We are proud people and not victims, so we don’t need to remind everyone.” Or, “America is ashamed of how they treated us.”

Regardless of the reason, this is a story that needs to be told, especially during today’s political climate and debate on modern (legal and illegal) immigration.

Why did Italians Immigrate to America?

I always simplify this question with the following: Imagine Canada, United States, Mexico and Central America become one big country tomorrow, and the seat of government goes to Canada. Now everyone down to the most southern tip of Panama has to learn French. Also, the Canadians despise the Central Americans, so no money trickles south, so the Latin-American countries grapple with stifling poverty and crime, with very little oversight. It is a similar concept in Italy: Northern Italians generally have European blood, while Southern Italians and Sicilians have Mediterranean blood. To this day, many Italians do not consider themselves the same people, even though they are now unified under one flag.

This is an absurdly abridged version of the “Risorgimento,” or “Unification of Italy,” which was a complex and gradual process spanning much of the 19th century. It transformed the Italian peninsula—a patchwork of independent states, foreign-controlled territories, and the Papal States—into a single nation-state by 1861.

Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor, Your Huddled Masses

America seems to open its doors when we need workers of votes. Luckily for the Italians, slavery was just abolished in the U.S. so, who better to work the plantations than the Italians from the olive and citrus fields back home, who were so desperate that they would work for pennies a day? Also, cities were being built. Who do you think were the driving labor force of the era, digging subway tunnels, paving streets and laying bricks? And those railroad tracks out west can’t build themselves. This is not to diminish the extraordinary contributions of other immigrant groups at the time, but Italians are the main focus for this article.

Immigration Then Vs. Now

Without getting into a debate about the pros and cons of today’s immigration laws, ethics and attitudes, things have changed quite a bit. While systemic barriers persist, legal and societal advancements have mitigated the extreme exploitation and violence of the past. Modern immigrants have subsidized financial safety nets and protections that were not available to European, Asian and Latin-American immigrants of the past.

- Immigration Act of 1891 established federal control over immigration and barred those with contagious diseases, criminal backgrounds, or those deemed unfit for work. Having a job or sponsor lined up, and/or being able to prove financial stability, got you to the top of the list, and lessened the very real risk of being turned away.

- The 1907 Immigration Act introduced further restrictions, such as barring those with mental or physical disabilities that could make them dependent on public funds.

- The 1917 Immigration Act (also called the Literacy Act) introduced a literacy test, requiring immigrants to read and write in any language.

- The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 introduced nationality-based quotas, limiting immigration to 3% of the number of each nationality present in the U.S. in 1910.

- The Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act) reduced quotas further to 2% of the 1890 population of each nationality, favoring immigrants from Western and Northern Europe while severely limiting those from Southern and Eastern Europe (essentially, Italians and Jews).

The Padrone System

If you were a poor family thousands of miles from America, and had no connections to the New World, how would you get a foot in the door with such restrictions? In the case of Italians, many went through the “padrone” system. This was a labor arrangement exploited by Italian immigrant labor brokers, known as padroni (singular: padrone), who brought Italian workers, including young boys as young as 5-years old, to the United States. This system was both a pathway to America and, for many, a trap into conditions of indentured servitude. Many Italian families in Southern Italy, burdened by poverty, sent their sons to America with the help of a padrone, who promised job placement and housing in exchange for a portion of the boys’ wages. While the padrone provided critical support for some, for others, it was an arrangement rife with abuse, especially for children. Note that the majority of padroni were northern Italian.

The Exploitation of the Padrone System

Upon arrival, Italian children were often funneled into demanding jobs with little control over their wages, living conditions, or work hours. Many were placed in physically demanding roles—such as street sweeping, construction, or factory work—while others were forced to work as street musicians, peddlers, or flower sellers. The padroni would often take a significant cut of the children’s wages, sometimes withholding nearly everything, and impose harsh penalties if they failed to meet quotas. This system effectively trapped the children in a cycle of debt and dependency, making it difficult to escape.

For those who attempted to flee or who were no longer useful to the padroni, homelessness and poverty awaited. Abandoned and vulnerable, many of these children became part of the growing population of homeless orphans in cities like New York, with few options for help.

[NOTE: If you are very interested in this time period, please watch CABRINI (2024). Sent from Italy, Mother Cabrini worked tirelessly to provide relief for runaway and abandoned Italian children on the streets on NYC. She founded orphanages, schools, and hospitals, creating safe havens for orphans and at-risk youth who had nowhere else to go. It is a beautiful movie and the best representation I’ve ever seen on screen of the Five Points/Little Italy.]

A Great Experiment in Human History

By 1900, the Lower East Side of Manhattan became one of the most densely populated districts on the face of the earth. Over 400,000 people per-square-mile in some wards (compared to an average of 70,000 people per-square-mile today). What happens when you take humans that have never met each other—or worse—have been at war with each other for generations, and house them all within a 2-square mile tract of land in Lower Manhattan?

In the case of Italians, immigrants sifted themselves block-by-block by the regions and villages they came from back home. Sicilians along Elizabeth Street, Neapolitan along Mulberry, and so on. The only thing uniting them was the new Italian flag… Outsiders saw them all as “Italian,” but immigrants still saw themselves as Canadian, Mexican, Panamanian, etc (a reference to the analogy earlier in the article).

Of course it became a very clannish and segregated micro-society, and with that, came some inevitable violence. It did not help that some criminals leaked through the system and were terrorizing the communities. The Black Hand (La Mano Nera), from Northern Sicily, set up shop, and national newspapers were picking up stories of extortion, bombings and barrel murders. This only made outsiders say, “They are all animals, let them kill each other,” leaving the 99% of the honest immigrant population helpless, completely untrusting of outsiders and even each other.

Anti-Italian Discrimination

Italians encountered widespread discrimination rooted in nativist prejudices, racial stereotypes, and economic anxieties. Perceived as culturally and racially inferior, Italian immigrants faced exclusion, violence, and systemic marginalization. Southern Italians looked unlike any other European group to arrive to the Americas before: Dutch, English, French, German, Irish, and so on. All Norther European. However, Mediterranean Italians are generally darker, and easier to stand out in a crowd—so they were easy targets to begin with.

Sensationalized media coverage, including newspaper illustrations, reinforced the association of Italians with organized crime, violence, and laziness. These stereotypes ignored the diversity of the immigrant population, 99% of whom were laborers seeking honest work.

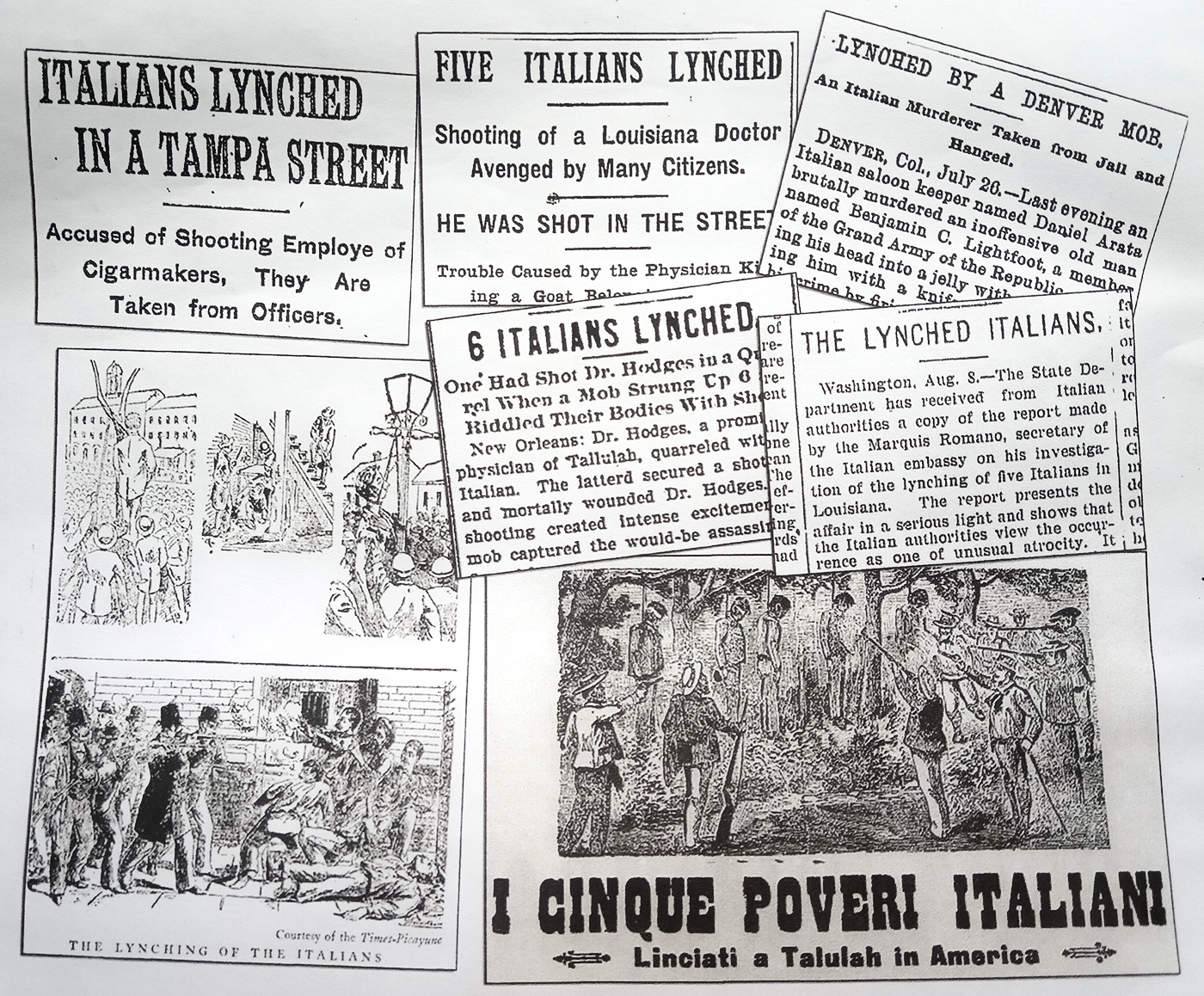

Lynchings

Yes, Italians were lynched in America, as well as Asians, Mexicans and First Nations People. I know it is not taught in school. As far as lynchings go, exact numbers are difficult to pinpoint. It seems that every source I find varies by sometimes hundreds of incidents.

Many Italian lynchings were not systematically recorded by institutions like the Tuskegee Institute, which focused on Black and White victims, often lumping Italians (as well as Mexicans) with “other Whites.” Names and dates can vary across sources due to anglicization or poor documentation. Between 1877–1950, around 1,200 “White” individuals were lynched, with most occurring before 1920. A further 200+ Asian Americans and 3,000 Black Americans were lynched during that time period.

Some of the following incidents may stem from oral histories or local records, so this is not an exhaustive list by any means, but these are names and incidents which have been forgotten over time.

July 27, 1873 – Trumbull, OH: Giovanni Chiesa, the first documented Italian immigrant lynched in the U.S., was killed by a mob. He was among a group of Italian immigrants brought in as strikebreakers, which created tension with the existing (mostly Welsh) miners’ union.

March 26, 1886 – Vicksburg, MS: Federico Villarosa and Rocco Gerbino, Sicilian immigrants, were lynched after dubious accusations of assaulting a minor.

1893 – Denver, CO: Daniele Arata was lynched for killing a man in a drunken bar fight.

1893 – Lake City, FL: Three Italian grocers—Antonio Pons, Joe Pons, and Vincent Pisano—were lynched after a credit dispute with a local doctor.

March 11, 1895 – Walsenburg, CO: Three Italians were lynched after a brewer’s murder; only one had confessed.

March 14–15, 1891 – New Orleans, LA: Eleven Italian immigrants (including Antonio Bagnetto, Joseph Macheca, and the Monasterio brothers) were massacred by a mob after their acquittal in the murder of Police Chief David Hennessy.

August 8, 1896 – Hahnville, LA: Three Italian immigrants were dragged from jail and lynched for allegedly murdering a store owner; two were jailed on unrelated charges.

1896 – Tangipahoa Parish, LA: Angelo Incardona, a Sicilian merchant, was lynched after a theft accusation tied to economic rivalry.

July 20, 1899 – Tallulah, LA: A Sicilian immigrant family (commonly cited as the Giarratano family, with 5–6 victims) was lynched over a dispute involving a goat.

1898 – Spring Valley, IL: Frank Pietro, an Italian coal miner, was lynched during a labor strike.

1901 – Erwin/Durant, MS: Giovanni Serio, his son Vincenzo, and possibly Salvatore Serio were ambushed and killed over a cotton-picking contract dispute.

1901 – Mississippi Delta, MS: Antonio Monticciano, an Italian laborer, was lynched after a wage dispute with a plantation owner.

1907 – West Plains, MO: Salvatore Romano, an Italian railroad worker, was lynched following a labor confrontation.

1907 – Rayville, LA: Salvatore Arena was lynched after being accused of murdering a white woman; no evidence was presented.

1910 – Tampa, FL: Rafael De Rosa, an Italian grocer, was lynched without trial after being accused of assaulting a white woman.

1910 – Tampa, FL: Angelo Albano was lynched amid tensions in the cigar industry after a deputy’s murder.

1915 – Monongalia County, WV: Joseph Vitali, an Italian coal miner, was lynched during a labor dispute after a mine superintendent’s death.

1915 – Hahnville, LA: Charles Lentini, an Italian laborer, was lynched on unproven accusations of assaulting a child.

December 14, 1916 – New York City, NY: Paolo Boleta was beaten to death by a mob after firing a weapon; newspapers compared him to a “friendless Negro.”

1920 – Tallahassee, FL: Joe Romano, an Italian grocer, was lynched after being falsely accused of murder.

1922 – Sanford, FL: Frank Emmolo, a citrus farmer, was lynched after a land dispute where he allegedly shot a neighbor in self-defense.

How Italians became “White”

For centuries, Italians existed in an ambiguous racial category—neither fully “White” nor grouped with Black, Asian, or Indigenous communities.

This murky status was further complicated by legal debates. The 1790 Naturalization Act restricted citizenship to “free White persons,” and courts grappled with whether Italians qualified. Their path to inclusion relied heavily on assimilation. Over generations, Italian-Americans adopted English, moved to suburbs, and intermarried with other European ethnic groups. Economic mobility, fueled by union jobs, GI Bill benefits, and entry into skilled professions, allowed them to blend into the White working and middle classes. By World War II, their patriotic contributions—both on the battlefield and the home front—helped reframe Italian-Americans as loyal citizens, distancing them from stereotypes of “foreignness.”

The Civil Rights era of the 1960s solidified their place within the expanded boundaries of “Whiteness.” As racial tensions centered on the Black-White debate, Italian-Americans were increasingly folded into the “White” majority. Meanwhile, pop culture began portraying Italian-Americans in more mainstream roles. Essentially, non-Italians started to realize that they like listening to Frank Sinatra and eating pizza. Though media tropes like the “mafia stereotype” persisted, these representations ultimately reinforced their assimilation into American identity.

I did not hurt that other impoverished and opportunity-seeking immigrant groups started migrating to America after WWII, as working-class Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Mexicans, Chinese and others started filling the roles of factory- and farm- workers, that Italians were leaving behind after generations.

SUGGESTED FURTHER READING

- Rope and Soap: Lynchings of Italians in the United States, Patrizia Salvetti

- Wop! A Documentary History of Anti-Italian Discrimination in the United States, Salvatore J. LaGumina

- La Storia: Five Centuries of the Italian American Experience, Jerre Mangione and Ben Morreale

- Are Italians White? How Race is Made in America, Jennifer Guglielmo and Salvatore Salerno

- Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White, David R. Roediger

- The Business of Crime: Italians and Syndicate Crime in the United States, Humbert S. Nelli

- Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race, Matthew Frye Jacobson

[FEATURED IMAGE: Italian immigrants, Photograph by Edmunds E. Bond, ca. 1915. Courtesy of the Trustees of Boston Public Library]

Eric is a 4th generation Lower East Sider, professional NYC history author, movie & TV consultant, and founder of Lower East Side History Project.